Judenburg

History of the Jewish community of Judenburg

- Latest Writings, Writings

// Year:

2015

// Reprint:

2022

// Publications:

First edition: Media-Archive Notebooks #1, Studies, September 2015

Second edition: Media-Archive Notebooks #1, Studies, November 2016

Third edition: Media-Archive History | Judenburg – Documents from the Diego Cinquegrana Collection on Antisemitism, February 2022

// Author:

Diego Cinquegrana

// Details:

Short essay on the history of the Municipality of Judenburg (Austria) and on the evolution of the local Jewish presence over the centuries. Previously published in ‘Media-Archive Studies # 1’ (September 2015), it is presented here in a new, revised and extended version.

// Credits:

© 2015 – 2022 Diego Cinquegrana | Media-Archive History – All rights reserved | thegoldentorch.com

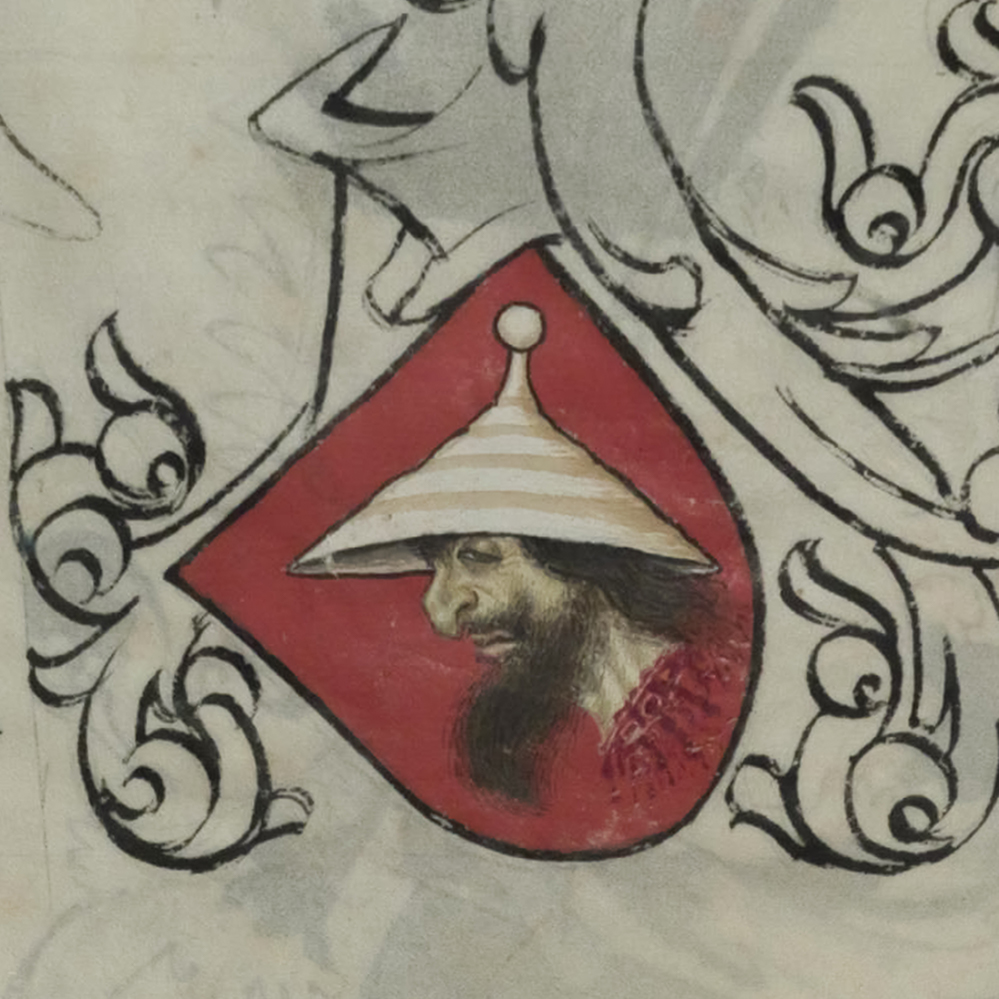

Seen from the perspective of the imaginary and stylistic features adopted by anti-Jewish propaganda over the centuries, it is certainly a singular case to come across the historical coat of arms of a city in the Land of Styria (Austria), above which the profile of a Jew leaning on a red shield and adorned with a pointed hat (Judenhut); this is the case in the city of Judenburg.

With notable variations in style and attributes, this representation is attested in various documents starting from the precious collection “Österreichisches Wappenbuch” of 1445, where the severed and bloody head of a Jew on a red field is surmounted by a hat with alternating white and yellow stripes [Fig.1]; a particularly bloody and connoted representation, probable echo of the anti-Jewish riots of the twenty years that preceded its realization and anticipating the expulsion decree of 1496.

A different representation appears in the subsequent “Wappenbuch des Zacharias Bartsch” of 1567, this time it is the face of the Jew that is bleeding, surmounted by a hat whose color changes abruptly to blue [Fig.2 and following]; this last iconography is re-proposed almost similar also in the collection “Sammlung von Wappen aus verschiedenen, besonders deutschen Ländern” of 1600, but deprived of the most cruel details [Fig.3]; it will probably be the latter ‘more secular variant’, devoid of anti-Semitic creed, to act as a matrix for the coats of arms prior to the end of the nineteenth century [Fig. 4] and for the one still in use today.

The anti-Semitic clamors of Europe in the late nineteenth century, outposts of the variegated National Socialist anti-Semitic imaginary, reawaken the ferocity of the fifteenth-century coat of arms, which we find reproposed in a Reklamemarke of the “Verein Südmark” of Graz (1889) [Fig. 5 and following]. In this last representation, the juxtaposition and deformation of a few but essential features reveals the völkisch and anti-Semitic character of the association already declared through the brief and lapidary commandments imprinted on the issues of emergency currencies: „Erneuerung unseres durch tiefen sittlichen Verfall bedrohten Volkstums durch Erziehungs und Bildungsarbeit auf arischer Grundlage ” (“Renewal of our people, threatened by profound moral decay, through an educational work on an Aryan basis”).

Following the Anschluß it will be the primeval coat of arms shown in the collection “Städtewappen des Österreichischen Kaiserstaates” by Vincenz Robert Widimsky of 1864 [Fig. 6] to act as a watershed between the pre and post war representations, rising to the role of new and de-Judaized emblem of the city; the latter will be in use from September 1939 until the end of the Second World War [Fig.7 and following].

The decision to formalize the historical coat of arms [Fig. 8 and following] dates back to June 1959 and, in contrast to the (probable) intentions of the previous iconographies, wanted to pay homage to the contribution of the Jewish community in the history of Judenburg, whose name suggests stories and information about his past.

The name Juden-burg, could be translated as “The fortress of the Jews” [Fig. 9 and following] or more properly “the village of the Jews”, referring to the area intended for merchant trade near the castle of Eppenstein not far from the small town. That the origin of the name can be univocally traced back to the presence of a primeval Jewish community in the territory around the year one thousand is the subject of discussion, we find it attested as early as the 12th century in various forms: “Judinburch” (1074), “mercatum Judenpurch” (1103), “Judenburc” (1147), “ecclesia de Judenburg” (1148) and “Judenwurckk” (1363). but according to the state of the sources we can confirm the continuous presence of a commercially active Jewish reality only starting from 1300:

March 8, 1340, extinction of the debt contracted by Heinrich, Bischof von Lavant with “Der Jude Davit aus Judenburg”:

Der Jude David (Davit) aus Judenburg und seine Erben of him bekennen, dass Ulrich von Haag und seinen Erben sämtliche Schulden, die sie bei David hatten, zurückgezahlt haben. Alle Urkunden, die weitere Ansprüche Davids und seiner Erben an Ulrich oder seine Erben beweisen sollen, werden für ungültig erklärt.

Siegel Ulrichs von Wallsee [-Graz] auf Siegelbitte des Ausstellers angekündigt.

June 2, 1343, extinction of the debt contracted by Ulrich von Haag with “Der Jude Höbssel aus Judenburg”:

Der Jude Höschel (Höbssel) aus Judenburg bekennt für sich und seine Erben, dass Heinrich [III.], Bischof von Lavant und früherer Propst des Kollegiatsstifts St. Virgil zu Friesach, alle Schulden, die Heinrich oder dessen Vorgänger bei ihm- hatten, gezahlt hat und sagt Heinrich und dessen Kirche ledig.

Finding towns with compound names (such as Judendorf or Judenbach), is very common in the territories of Germany and Austria and, as one might expect, all historically attest to a strongly rooted Jewish presence and particularly significant for the growth of the social-economic apparatus of cities.

The commercial fortune of the Judenburg area originates from the mining in the Falkenberg quarries, from which, already in ancient times, iron ore was extracted for smelting and processing; this situation favored the settlement of man and the evolution of social forms already from the early Bronze Age. At the end of the 19th century. important archaeological excavations brought to light precious artifacts dating back to the Haltstatt culture, dating back to around 600 BC. such as the “Strettweg chariot” (Strettweger Kultwagen) [Fig.10 and following], which is part, together with other objects of very precious workmanship, of the funerary equipment of a princely tomb.

Over the centuries, the culture of Haltstatt progressed rapidly and thanks to a flourishing commercial activity it spread throughout much of Europe, from Great Britain to Slovakia, also engaging in commercial activities with Greece and Etruria.

If ‘The Occident’ (1868) informs us of the discovery of a pre-Roman tombstone bearing a Hebrew inscription dating back to 314 BC. and the discovery of the treasure of Judenburg-Strettweg (about 3,000 Antoninians), now preserved at the “Münzkabinett Schloss Eggenberg”, echoes the disturbances of the third century crisis, is a particularly exceptional archaeological discovery to fix the certain date of the presence Jewish in Styria as early as the 3rd century: the Halbturn Amulet [Fig. 11], found in the town of the same name located just over 200 km from Judenburg.

The precious phylakterion was found by the archaeological team of the “Institut für Urgeschichte und Historische Archäologie” in Vienna, in the tomb of an eighteen-month-old girl located inside a 3rd – 5th century funerary complex. The gold leaf, just 2.2 cm long, was contained in a silver capsule presumably placed around the neck of the deceased at the time of burial. Unique of its kind, the lamina differs in content from other apotropaic amulets found in the region, in fact it bears an inscription in Greek letters attributable to the ancient Hebrew prayer Sh’ma Yisrael: “ΣΥΜΑ ΙΣΤΡΑΗΛ ΑΔΩNΕ ΕΛΩΗ ΑΔΩN Α”.

[Deut. 6: 4]

.שְׁמַע, יִשְׂרָאֵל: יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ, יְהוָה אֶחָד

Listen, Israel: the Lord is our God, the Lord is One.

Judenburg’s commercial prestige was strengthened in the centuries to come and, from the Middle Ages onwards, it increasingly confirmed its character as a strategic outpost within the trade routes that connected Venice to the cities across the Alps. Already in ancient times, products from the Mediterranean and later from the East were imported and, in addition to ferrous minerals, Celtic Valerian, a plant whose essential oils were used in perfumery, were exported.

If the information about the presence of settled Jewish communities in Europe before this period is rather sporadic, in the following centuries it will become more and more concrete: it dates back to 321 AD. an important edict of Constantine I applied to Cologne, through which it allowed Jews to hold official positions in the municipal administration, such a privilege presupposed the establishment of a community important enough to be able to bear such a responsibility, especially in economic terms: “Through a law that applies to the whole empire, we allow all city councilors to appoint Jews to the governing body of the city […] “.

For the European Jewish communities the Middle Ages was a period of particular cultural and commercial activity, the testimonies between the 6th and 12th centuries. A.D. are numerous, such as the customs charter of Raffelstatten (late 10th century), the gravestone of shabbethai ha-Parnes (12th century) now preserved in the Landesmuseum Kärnten in Klagenfurth and the famous ‘monetarius’ such as Shlomo of Regensburg, Master of Coinage of Duke Leopold V of Babenberg, David haCohen of Münzenburg, Master of Coinage under Frederick Barbarossa and Yechiel bar Shmuel of Würzburg Master of Coinage under Otto I. von Lobdeburg, praised on his tombstone as איש נכבד (man of honor).

In the thirteenth century the position of the Austrian Jews will be consolidated by an active participation in important positions, such as the administration of minting, taxes and trade and the “coexistence” with Christians will be facilitated by the issuance of important decrees by of Frederick II Hohenstaufen (1238), such as the prohibition of baptizing Jewish children against the will of their parents and of Frederick II of Babenberg (1244) who will regulate relations between Jews and Christians guaranteeing various privileges including the detention of pawn shops ( properly administered) and a complete revision of private law, as expressed in the 30 points of the “Privilegium Fridericianum”.

In 1224 Leopoldo VI of Babenberg granted Judenburg the title of city, an important change that would determine the extension of the city’s territorial limits, economic and administrative independence and the expansion of commercial activities. This event will be philatelically remembered on April 24, 1974, when the Austrian post office will issue a stamp (bearing the coat of arms of Judenburg) in memory of the 750 years of the acquisition of the title of city [Fig. 12 and following].

The new social and economic framework, the growing mercantile activity together with the privileges granted during the 13th century will greatly strengthen the rights of the Jewish community present on the territory but at the same time will lead to the inevitable worsening of the tensions between Christians and Jews, accused, according to the custom of the time, of usury and heresy.

In 1312 there was a violent insurrection against the Jews of Fürstenfeld and Judenburg, the trigger was the rumor that the Jews had plotted to kill all Christians on Christmas night and it was rumored that the plan had been revealed by a Jewish girl who was having an affair with a Christian. Once the massacre was complete, the last remaining Jew would have been hanged at the city gate, later called Judenthürl. The intervention of Duke Albert II of Habsburg mitigated anti-Semitic persecutions and massacres but a false accusation of Hostienschändung (desecration of the host) of 1338 was enough to burn alive over 70 Jews from the Wolfsberg community, not far from Judenburg.

The same occurred during the Black Death: although the Jews enjoyed the ducal protection (eager for the profits generated by the interest rates granted to pawn shops as early as the privileium of 1244), the violent insurrections that broke out across Europe against the Jews also struck Austria (albeit to a lesser extent); in Krems, seat of an important community, hundreds of Jews were burned alive in their homes on St. Michael’s Day (29 September 1349); Duke Albert II, despite not having been able to stop the massacre, arrested those responsible and those who did not die in prison suffered heavy deprivation. Despite the violence of 1312, the Jewish presence continues to be attested in the documents of the following years, where we read of the debt contracted by a certain Heinrich von Kranichberg to the Jew Hoeschel residing in Judenburg (1331), a very prominent figure, ( protégé of Otto IV of Habsburg) who had financial relations with the high nobility of Carinthia and whose descendants (sons Lesir and Nachman) continued the work, financing for example, in the case of Nachman, the bishop of Bamberg.

The position of the Austrian Jews will worsen significantly under the power of Albert III and Leopold III of Habsburg who will cancel all credits, confiscate property and apply heavy restrictions to the economy of the communities, up to intimidating incarcerations in order to extort money for the taxes. Between 1420 and 1421, a new accusation of “profanation of the host” [Fig. 13], will decree, under Albert V of Habsburg, the complete destruction of the Jewish community of Vienna, children will be forced to baptism or reduced to slavery, 92 men and 120 women will be burned alive and a mass suicide will be consummated in the Or-Sarua synagogue; the detailed testimony of these tragic events, known as “Wiener Geserah” (Viennese decree) was recorded in a chronicle written in all probability close to the events of 1421.

At the beginning of the 15th century About 60 Jews lived in Judenburg with a considerable dowry and in the second half of the 1400s, documents of the time report that the Jew Cham owned 6 houses and his co-religionist Manl 3.

New accusations against the Jews, including that of the ritual murder, which had already reached notoriety following the case of San Simonino, led Maximilian I of Habsburg to decree the expulsion of all Jews from the Land of Styria and Carinthia in 1496 (subject to compensation for the economic damage that this would have inflicted on its coffers).

Following the expulsion of the Jews from Styria, the Jewish community of Judenburg ceased to exist definitively until the second half of the 19th century, when a small congregation (about 90 Jews in 1880) reappeared, affiliated with the Graz community, with a prayer hall and a cemetery, built in 1873 and destroyed by the Nazis in 1942.

The Jewish survivors of the Holocaust will return to Judenburg after the war, where a DP-Camp (transit camp for displaced persons) was set up there, administered by the UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration) and by the AJDC (American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee), retracing back that road that centuries earlier had led them to found one of the many precious lost Jewish communities in medieval Europe.

The collection

A small preview of some of the objects contained in the collection. The entire collection is published in the volume: Judenburg – Documents from the Diego Cinquegrana Collection on Antisemitism, Media-Archive History, 2022.